Media screen troubleshooter: color changes with media screen breakpoints. Disable in global CSS.

First, I’d like to welcome you to my Endosym blog post! Here I will explain how the series was developed, take you to the jungles of West Africa, raise difficult questions and hopefully generate a dialog between us.

The concept of an Endosym—a demon-possessed human—came to me during my first tour in Liberia. I was assigned to the US Military Mission to Liberia as the Engineer and G-5 advisor to the Armed Forces of Liberia. The United States had provided military advisors to the Liberian Army since the early 1950s. When I arrived, the US Military Mission to Liberia had twenty members. Six members were on a two-year assignment with their families. Another twelve were on a twelve-month unaccompanied tour.

Being without their families, the advisors on twelve-month tours worked directly with the Liberian units, living in Liberian army camps. My assignment was to Camp Jackson, a base located on the border between Guinea and Liberia, which is about 180 miles from Monrovia, the Liberian capital. The Liberian Engineers and Artillery were stationed at Camp Jackson. One US Army Officer and two non-commissioned officers were assigned to Camp Jackson. Three 10 feet by 40 feet trailers had been moved to Camp Jackson.

Camp Jackson trailers

Camp Jackson trailersThe trailers were positioned in a U shape with a screened porch built between them. There was no electric power to the camp; a 5KW generator provided power for the well and radio. It was run for only a few hours each day. The Liberian army was primitive by US standards, their main weapon being the old, venerable M-1 Rifle.

Three weeks after I arrived at Camp Jackson, the two NCOs’ tours ended. When replacements did not arrive, a radio call to Monrovia confirmed that replacements would never arrive. The United States was reducing the size of the Military Mission to six and the reduction would be through attrition. For the remaining eleven months I would be living alone at Camp Jackson. Let me tell you, for a white kid from Spokane Washington, where there was one black in my senior high school class of six hundred students, I was already in cultural shock. Now, I found myself alone.

The staff in Monrovia scheduled five days a month where I would come to the Capital to report on the Liberian units’ progress in training and stock up on supplies—probably also to see if I was still of sound mind and had not gone totally native. Thus began the most unique tour of my entire military career.

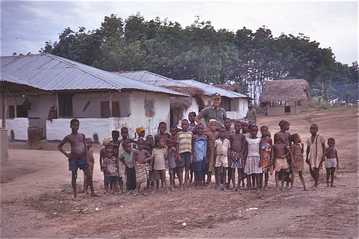

Author and children at Camp Jackson

Author and children at Camp JacksonI would live with the 500 soldiers and their families. They would be my only comrades. I would drive over 11,000 miles in the British Land Rover provided to me by the Liberian Army. I would cover every mile of road in the interior of the country and walk into remote villages where few whites had ever visited.

The mission of the units at Camp Jackson was to provide security along the border between Liberia and Guinea. At the time, Guinea was a communist controlled country and Liberia was pro United States. The engineers at the camp would also assist in building farm-to-market roads linking villages to the main road. The artillery unit would conduct all its live training at the camp’s firing range.

From what I was told, past advisors worked with the troops during the day and the rest of the time stayed in the trailers. When you have no one to talk to, you immerse yourself in the culture. I had been back from Vietnam three years and it just seemed logical that I would accompany the soldiers on patrols. Besides, what else was there to do? I found the Liberian people to be friendly and outgoing, and they accepted me as one of their own.

Over the months, when I expressed an interest in their culture, I was shown aspects of the life of Liberians that visitors never see. Since the national language was English, it was easy to be accepted in any village. Soon, I was able to walk freely through the camp and nearby village of Naama, accepted as a part of the village. I took pictures of the sacred places, and even the old people—who feared that their spirits could be captured by cameras—allowed me to take their photos. It was amusing when I went to Monrovia; I would find myself staring at a white person on the street. Without a mirror, you begin to feel black.

During training I always ate the noon meal with the troops, and several evenings a week I would eat at the officers’ huts with their families, always asking questions about their culture. I could even tell the differences between the tribes. Contrary to the stereotypical dogma, not all blacks are alike.

I learned of the reasons for hostilities between the tribes and was amazed at how the history of the tribes was passed from generation to generation. One of the most interesting aspects of the society was the belief in witchcraft. Over time, I will introduce the readers to several events that occurred that caused me to believe that there are some things that cannot be explained.

In this introduction let me provide you with one story. As the only advisor still living in the interior, I would often find myself hosting visiting military and civilians from the United States. When VIPs wanted to visit, I would meet with the post commander and town chief and set up a ceremony. It was funny, when young Liberian women dress up they wear a bright Lappas pulled up over their breasts. So I had to explain that for the visitors who in most cases were middle aged men, I wanted all the young women wearing the Lappas around the waist—nothing like young topless teenage girls to make the visit of an old US Army General memorable.

Sacred tree in village

Sacred tree in villageTrees are considered spiritual beings to the Liberian. Large trees in the center of the village were special and I should have known that. Also, high-ranking people who die in the village are sometimes buried near a tree in the village. This tree was unusual, with large tubular fruit hanging from it. Anyhow, we stopped to admire the tree, and then the visiting officer asked that I take his picture next to the tree. But, I digress. On one occasion, I was showing another US Army officer a village along the border. As we walked through the village we noticed a tree in the center of the village.

Spirits surrounding the tree

Spirits surrounding the treeI had just finished taking the picture when an old man sitting on a bench next to a hut waved at us. We walked over and talked to him. It turned out that he was a retired judge from Monrovia. He had returned to his village to live out his life.

He explained that the founders of the village were buried under the tree and the fruit fed their spirits. No villager would dare go near or touch the tree for fear of angering the spirits. We apologized for our indiscretion. The old man laughed and said we had done no harm and he was certain that we had not angered the spirits.

When I developed my pictures, strangely something was there that could not be explained. In the first picture there appeared to be a translucent thing floating near the tree. Then, when the fruit was touched a swarm of things are swirling around the tree. The spirits had been angered.

During the year I lived at Camp Jackson I experienced a number of unexplainable events. Ask me and I will be glad to provide you with other stories.

OK, now you have an idea as the why I decided to write the series. But why endosyms? Where did that idea come from? Are you ready? Do endosyms really exist? In my next post, I’ll tell you about my first endosym.